The Northern Ireland Football Fund announcement was billed as Christmas Day for the football family in Northern Ireland, though many were left wondering if Santa Claus even exists. For the 20 football clubs that found themselves on the “nice” list, there were others left with nothing, not even a lump of coal. A mix of expectation, frustration and partial delivery has defined the story of football infrastructure in Northern Ireland. And it’s a story that didn’t just begin 14 years ago with the Sub-Regional Stadia Fund, but way back in 2005 when stadium development was first put on the political agenda.

NI football stadia missed out on the modernisation that occurred in England and Scotland following the 1989 Hillsborough disaster and the subsequent Taylor Report. With match attendances in Northern Ireland growing, and increased private investment entering the Irish League, the sport has untapped potential as a community, economic and social resource. But too often supporters attend stadia with poor, outdated, facilities.

How we got here

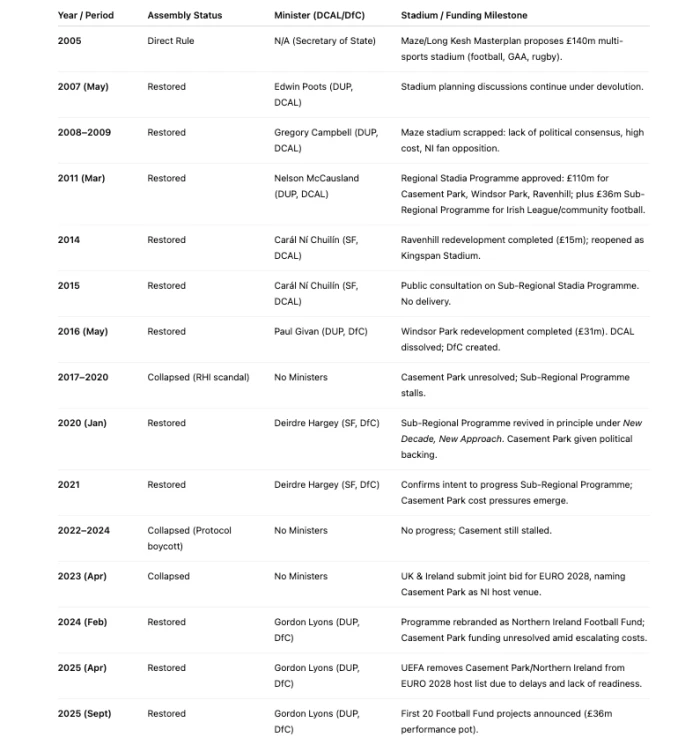

In the mid-2000s Northern Ireland’s stadium debate centred on the Maze/Long Kesh site, where a proposed £140m, 40,000-seat multi-sports stadium was to host football, rugby and GAA. Conceived as part of the Maze Masterplan under Direct Rule Ministers, it was promoted not only as a “shared future” project alongside a conflict transformation centre, but also as a way of bringing London 2012 Olympic football matches to Northern Ireland. Yet the plan soon became mired in controversy: unionist politicians and many Northern Ireland fans opposed it, with the contested politics and history of the site mixing with opinions on the the proposed stadium as oversized, soulless, disconnected from transport infrastructure, and too far from Belfast. By 2008 the project collapsed - officially over cost, but equally because there was no political or fan consensus to build a national stadium on such a contested site.

Once the Maze project collapsed, calls quickly came to ensure Northern Ireland still benefited from the Olympic Legacy, even without hosting - sounds familiar? When Casement Park fell out of Euro 2028 contention, the same script was dusted off: legacy without the games.

With the Maze project now off the table, a vacuum appeared with Northern Ireland’s three main sports - football, GAA, and rugby - still short on modern facilities. The solution? Step forward the Regional Stadia Programme. This programme created two distinct strands:

Regional stadia development - focusing on the three flagship grounds:

Casement Park (GAA)

Windsor Park (football)

Ravenhill (rugby)

Sub-Regional stadia development - a £36m allocation aimed at improving football grounds below Windsor Park level, particularly Irish League and community clubs.

Progress was uneven. Ravenhill was redeveloped and reopened in 2014, Windsor Park followed in 2016, but Casement Park became mired in legal challenges, delays and spiralling costs that continue today. Meanwhile, the Sub-Regional Programme stalled altogether. Despite the Executive commitment in 2011, and even a public consultation in 2015, no funds were ever released.

Only now, 14 years later, has this pledge been reborn as the Northern Ireland Football Fund, with the Department for Communities announcing the first 20 projects to proceed under the new scheme in 2025.

Northern Ireland Football Fund

The 20 successful clubs under the £36m NI Football Fund were divided into tiers of funding:

Tier 3 (Large projects, £6m+): Cliftonville, Glentoran

Tier 2 (Medium projects, £1.5m–£6m): Ballinamallard United, Ballymena United, Banbridge Town, Bangor, Carrick Rangers, Dergview, Dungannon Swifts, Glenavon, Larne, Lisburn Rangers, Loughgall, Newry City, Oxford Sunnyside

Tier 1 (Smaller projects, <£1.5m): Armagh City, Ballymacash Sports Academy, Lisburn Distillery, Queen’s University, Rathfriland Rangers

Criticism followed swiftly. A number of significant clubs were left out - including Ards, Coleraine, Crusaders, Derry City, Institute and Portadown. The two clubs without grounds, Ards and Institute, are left in a particularly difficult position. The North-West felt shut out, with Coleraine, Derry City, Institute and other smaller clubs omitted.

Politicians quickly seized on the fallout. SDLP MLA Mark Durkan launched a petition to force the Executive to review the process, questioning whether the allocations had been handled fairly and transparently. Others have called for the publication of the scoring matrix, which was accepted by the Minister and set the criteria for officials to assess each bid. Voices sympathetic to the Minister highlighted the difficulty anyone would face balancing different priorities when agreeing a complex funding criteria, with insufficient resources. It is also fair to note that clubs whose applications were strongly supported by party colleagues of the Minister were among the unsuccessful bids.

The overall sense is clear: while the Football Fund represents long-awaited progress, its first outing has, as yet, not swept away the frustration of 14 years of delay, and the process has sparked new grievances.

How things could have been improved

Who doesn’t love hindsight? Looking back, the scoring matrix behind the NI Football Fund could have been stronger if three additional criteria had been built into its framework

Regional Equity - The North-West was entirely excluded. This was a missed opportunity for “Project NI” to earn goodwill in Derry. Investment here would not just have addressed historic underfunding but also signalled that the football family across Northern Ireland is valued in its entirety.

International Profile – Coleraine Showgrounds and others play host to the SuperCupNI finals, one of the world’s best-known youth tournaments. A “profile/events” weighting could have recognised venues with international reach and ensured that facilities matched the stage they provide.

Minimum Requirements - Some clubs still lack floodlights, rely on portacabin changing rooms, or play within grounds edged by dangerous concrete perimeter walls. Safety should have been a non-negotiable baseline. The urgency was underlined when Carrick Rangers forward Paul Heatley suffered injuries colliding with a wall at Taylors Avenue. And this isn’t just a local problem: in England, 21-year-old former Arsenal striker Billy Vigar tragically died after colliding with a concrete wall at a National League ground. The FA has since launched an immediate review of perimeter wall safety. The same risks exist at some SuperCupNI venues - beyond the danger to players, the reputational damage to Northern Ireland if such an incident occurred would be enormous.

What happens next?

For the 20 clubs selected, success at this stage is no guarantee of funding. Each must first clear due diligence checks - covering feasibility, financial standing and legal compliance - before progressing to Outline Business Cases. After 14 years of delay, some planning permissions have long since lapsed, meaning clubs may need to restart from scratch.

For those excluded, the road is tougher. Minister Gordon Lyons has pledged to meet unsuccessful applicants to reassure them that their journey is not over and to head off any potential judicial reviews. Yet with £36m in the pot against project costs totalling more than £80m, disappointment is inevitable.

Minister Lyons faces a near £50m shortfall. His strategy appears twofold: keep unsuccessful clubs engaged through dialogue and defend the process in the Assembly, but the political storm may not be easily contained.

Ultimately, the real solution is not tweaks to the process but more money. Whatever criteria is used to select the winning bids there is simply not enough money in the pot to transform the game. Minister Lyons previously acknowledged £200m as the figure required to modernise football infrastructure across Northern Ireland. That might have been attainable had Casement Park been fully funded as a counterbalance, but with the GAA project still stalled football’s allocation remains inadequate.

The truth is, £36m was never enough - not in 2011 and certainly not now. Santa isn’t likely to turn up with the missing millions, so for now fans of the 20 successful clubs can only hope the Minister is across every “jot and tittle” of the NI Football Fund - enough to see these much-needed projects proceed without further delay, and avoid becoming yet another chapter in Northern Ireland’s long, stop-start stadium saga.

Aaron Vennard is a Managing Consultant with 15 years in Financial Services across New York, Chicago, Toronto, London and Dublin, and long-time Irish League aficionado and Portadown FC fan.

Pivotal Platform is a home for guest writers to contribute their perspectives on public policy debates in Northern Ireland. The views expressed by guest writers are not necessarily those of Pivotal.